David Hockney's iPad Drawings

David Hockney’s artistic trajectory, from painting and printmaking through to photography and digital drawing, is marked by continuity, creative reinvention and endless experimentation. While he remains an artist profoundly interested in historical tradition, his lifelong preoccupation with observation and mark-making has seen him take a boldly modern and wholly democratic approach to making pictures, choosing to embrace a wide variety of techniques, processes and practices in his prolific career. With the iPad as a medium, Hockney’s life-long dialogues with artists including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh remain as prevalent as ever, existing not as a departure, but as a continuation of art history.

If you are interested in adding to your collection speak to one of our art consultants now - email us at info@halcyongallery.com

Hockney鈥檚 interest in digital art and technology traces further back

Hockney’s engagement with digital art reflects a long-standing fascination with the convergence of technology and artistic practice. During the 1980s, Hockney began experimenting with digital media and computer-generated images, interested in their potential as new tools for visual expression. Though groundbreaking at the time, he found the technology slow and limiting in terms of its responsiveness, remarking that ‘You thought you would make a mark, but the mark wasn’t there, it came thirty seconds later, as though your pen had run out of ink.’ Following this he began using the new Quantel Paintbox, a pioneering system for digital image manipulation. Often regarded as a precursor to Photoshop, this graphic workstation enabled one to draw, colour and edit images directly on a computer screen, using a stylus and tablet. Hockney’s experimentation with technology has also extended into his Home Made Prints, created with a Xerox machine in 1986. Although the early machines were analogue systems, these ubiquitous, mass-produced copy machines could be found in offices everywhere, and this body of work represented the first time that Hockney used such a commonplace, everyday item to make artwork. At the time, the Xerox offered him the fastest method yet to create prints. He remarked that it was ‘the closest I’ve ever come in printing to what it’s like to paint.’

These explorations with digital technology and everyday machines ultimately culminated in Hockney adopting the iPhone in early 2008, before moving on to the iPad – with a screen approximately eight times larger – following its release in 2010. He immediately saw the device’s potential as a tool to make art, stating that the iPad made him draw even more than before. For Hockney, it was a medium which finally reconciled digital technology with the immediacy of traditional mark-making. As his experimentation with technology has continued to evolve, Hockney has demonstrated how digital processes can reinvigorate the act of seeing. ‘I love new mediums… I think mediums can turn you on, they can excite you: they always let you do something in a different way, even if you take the same subject.’

A new medium to engage with the past

In bringing iPad drawing to the fore of his artistic process, Hockney does more than merely expand his own practice; he challenges the established hierarchies of Fine Art mediums, which traditionally place the most importance on painting and sculpture. His use of the iPad as a primary medium places as much worth on the immediacy of digital mark-making as on the gradual build-up of an oil painting on canvas. In this digital medium, Hockney found a way to accelerate his practice. It is worth noting too, that Hockney’s digital drawings have featured in several galleries and sacred spaces. In the Royal Academy’s 2012 exhibition, A Bigger Picture, and in the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s current exhibition, David Hockney 25, major works made on the iPad are incorporated alongside traditional works, further positioning the medium as part of an ongoing artistic standard. In 2018, Hockney unveiled a new stained-glass window, The Queen’s Window, at Westminster Abbey, commissioned to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’s reign. While engaging closely with the stained-glass windows of Henri Matisse and Marc Chagall, Hockney designed his window digitally on the iPad, employing its backlit screen as an essential characteristic to envision the interplay of light and colour. Reflecting his modern approach to design, the commission demonstrates his ability to translate this small handheld medium into a monumental architectural scale.

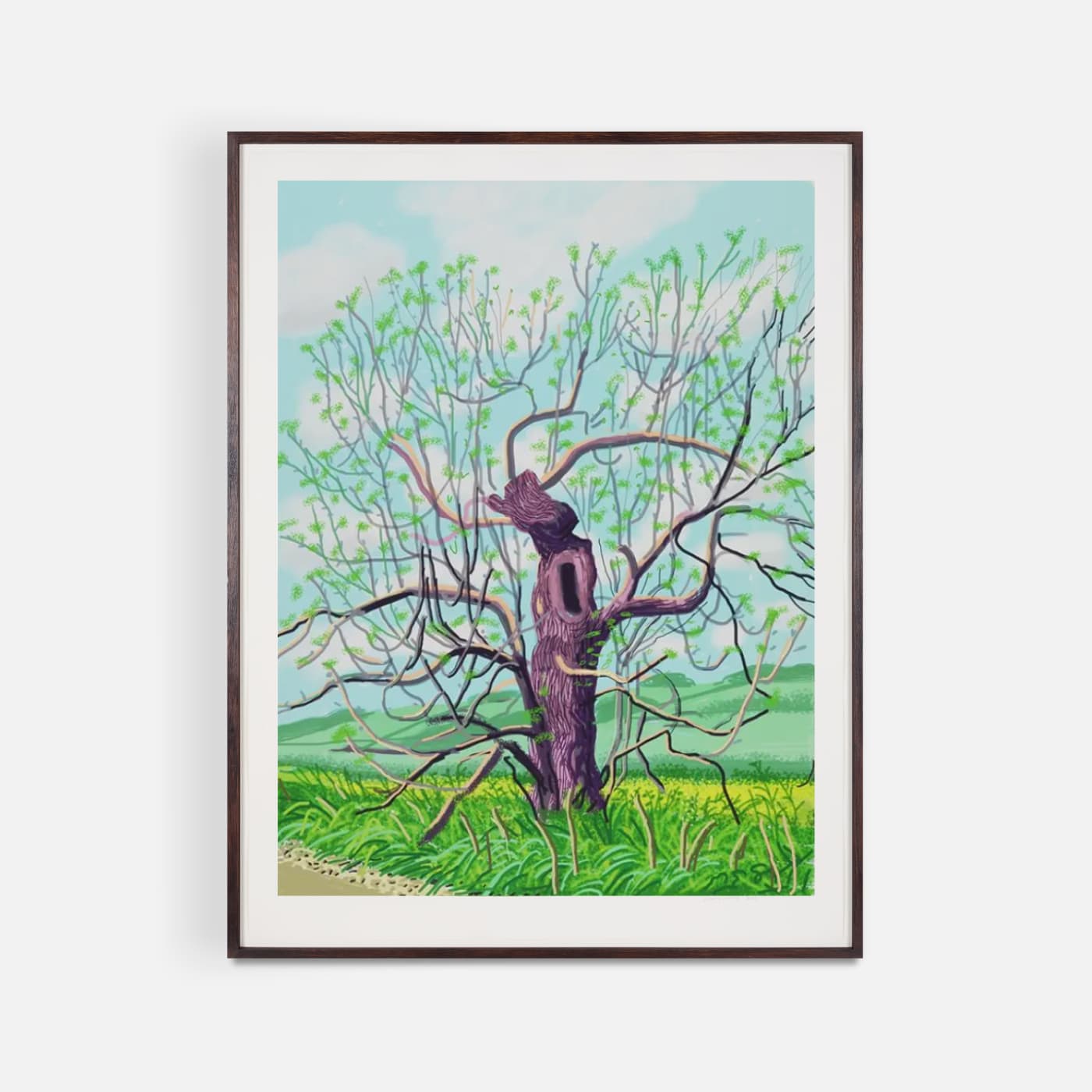

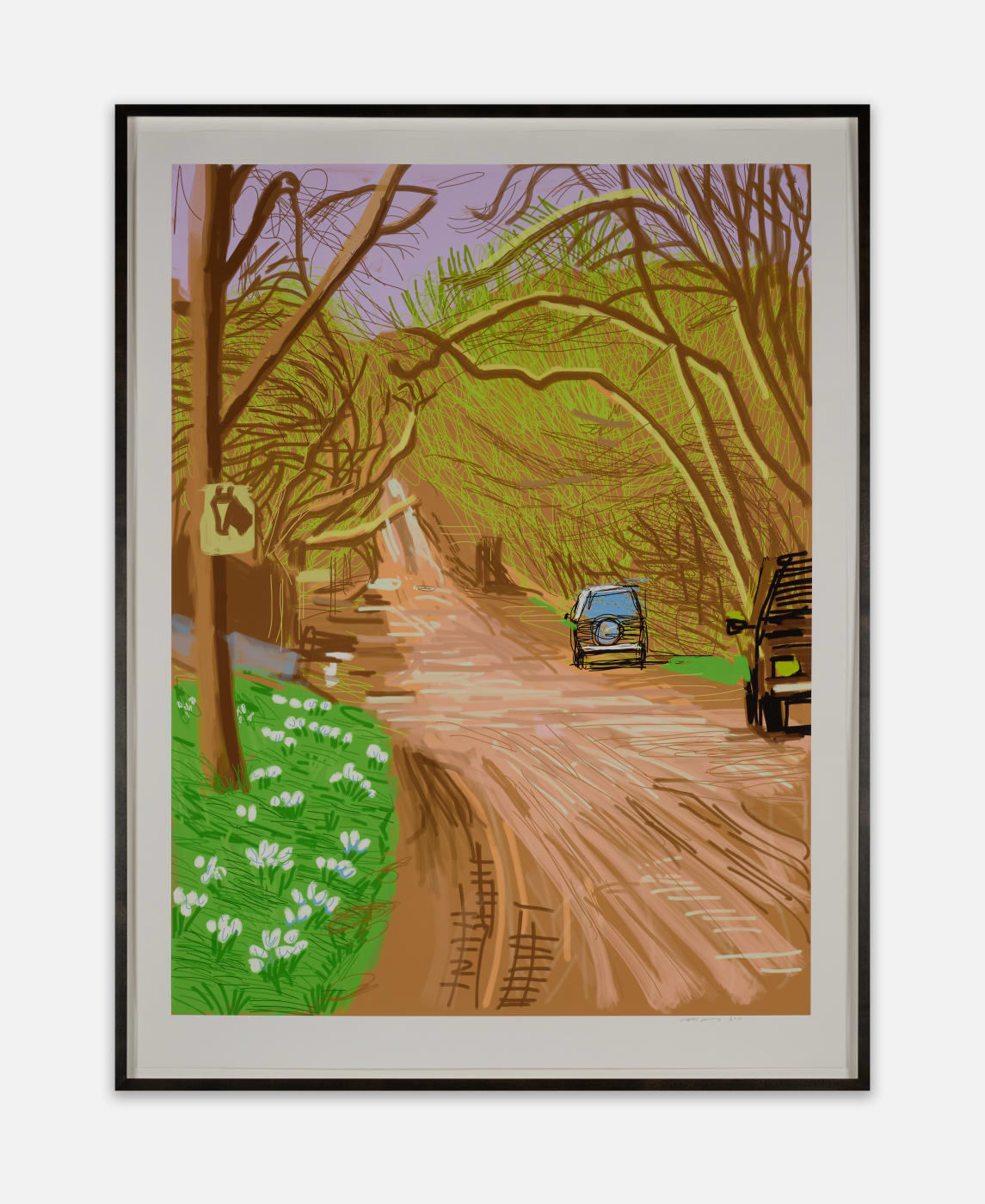

Hockney’s dialogue with art history continues in the visual language of the iPad drawings themselves. His use of highly saturated hues – enabled by the RGB colour palette of the digital screen – amplifies his bold colour choices, rendering scenes in radiant light which evokes the expressive intensity of Vincent van Gogh, the bold, flat forms of Henri Matisse, and the lush, imaginative landscapes of Henri Rousseau. Hockney’s vivid, expressive landscapes, floral arrangements and interiors, such as No. 778, 17th April 2011, do not seek to replicate nature with photographic accuracy, but instead communicate the mood, atmosphere and joy found in natural forms, directly echoing the Modernist sensibilities of the Impressionists and Fauvists. Through his iPad works, Hockney disregards the arbitrary and disciplinary boundaries of traditional artistic mediums, instead using digital tools to engage with art history, reimagining it for the 21st century.

The iPad allows Hockney to work en plein air in all seasons

The iPad’s inherent portability and responsiveness allow Hockney to work en plein air with a freedom that is inhibited by traditional media, especially in challenging outdoor conditions. The practice requires just the device and possibly a stylus, and is not susceptible to the same harsh weather effects as a pencil and sketchbook, or paint and canvas, functioning simultaneously as a sketchbook, a canvas and a recording device. The practicality and immediacy that the iPad affords is integral to his vision of capturing the landscape as a fluid and spontaneously shifting force.

‘Being in L.A. for thirty years, I’d never really watched a spring. You don’t really have a spring, I mean you don’t really quite have the seasons… They’re subtle… In northern Europe it’s a big change.’ - David Hockney

Hockney has a particular appreciation for returning to the same place, recording the same subject, and capturing the progressive shifts in light, weather, and colour over time. Made in Hockney’s native Yorkshire in 2011, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate series depicts a landscape in the midst of transformation, with a multitude of narrative layers that come with the changing seasons. In The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, 18th May 2011, the intense yellow of the rapeseed fields in the background signal that it is late spring. This picture is a celebration of growth; the trunk of the tree appears gnarled and nearly dead, but Hockney has captured it precisely at a moment in which new growth protracts from its branches just as it begins to bud. In this picture we also see Hockney’s ability to build depth and a layered perspective through the contrasting use of hard lines over soft forms. This can be seen in the precisely defined branches, accentuated against the soft, dappled fields and hills receding behind. Hockney does not shy away from emphasising the digital element of these works, frequently using dots along with fluid lines, referencing the same stylistic techniques that he has used in his etchings and lithographs. He is interested, above all, in recording the temporal powers of nature and the cyclical unfurling of the seasons, as winter makes way for the new growth of spring.

New technical provisions at his fingertips

Hockney began creating his iPhone and iPad drawings using the Brushes app, which offered a contemporary method for working en plein air, commenting that ‘the iPad is like an endless piece of paper’ at his fingertips. In fact, his iPad functions as much more than this, allowing Hockney to bring an entire studio in his pocket, complete with brushes, as well as the ability to adjust the softness of his lines, zoom in or out, correct, and layer digitally with a fluidity unattainable in traditional media. The influence of painting techniques is ever present – Hockney has even noted how when he first began finger painting on an iPad, he would instinctively wipe his thumb on his clothes before changing colour, the same way that a painter cleans their brush. The iPad drawings are also not constrained by drying times, and so his strokes become live gestures. Hockney says: ‘It now enables one to draw very freely and fast with colour. There are advantages and disadvantages to anything new in mediums for artists, but the speed allowed here with colour is something new. Swapping brushes in one hand with oil or watercolour takes time.’

Hockney has often highlighted the power of the bright, backlit screen as a characteristic which draws him to select particularly luminous subjects. This luminosity is something he cannot achieve with pencil and paper and is fundamental to the way he works and prints his artwork made on the iPad. There is a parallel here with a painting technique popularised in the 19th century by the Impressionists, who used a white ground layer on their canvases, resulting in enhanced brightness and more vibrant colours. J. M. W. Turner is thought to have been one of the key early proponents of this technique, and it rapidly gained popularity with the Impressionists who favoured the additional luminosity that it brought to their pictures.

Some of Hockney’s early works with the iPad used line sparingly to suggest light and shadow as a means of capturing the essential qualities of his subjects. Examples of this can be seen in Untitled (224) (Striped Mug), as well as Untitled 329, which uses rough and sketchy lines to illustrate the light as it hits the right side of the vase, passing through the glass and illuminating the shadow on the left. Hockney’s technical ability is also evident in the diffraction of the stems through the water. He uses a similarly loose technique to represent the texture in the flowers, leaves and stems, while in the background, he renders the depth of a tabletop purely by compressing his linework. Floral bouquets are recurring motifs in Hockney’s iPad drawings, and when he first began working with the medium, he would send his drawings to friends as gifts: ‘I draw flowers every day on my iPhone and send them to friends so they get fresh flowers every morning.’ Hockney’s former partner, John Fitzherbert, would buy a new bouquet every day to provide the artist with new inspiration and arrangements to work from.

The significance of mark-making and the artist鈥檚 hand in the digital age

One of the defining features of Hockney’s iPad drawings is his continued emphasis on mark-making and the importance that he places on the presence of the artist’s hand, even with a digital medium. While digital art is frequently associated with notions of detachment or automation, Hockney’s work represents the union of digital mediums with the physical act of drawing through expressive and gestural acts. Aside from the fluidity that the iPad allows him, he is drawn to its capacity to create a seemingly endless array of tactile brushstrokes, visible lines, textures and layers that mimic the variation of traditional drawing techniques.

Rather than striving for photographic realism, Hockney is far more interested in celebrating the immediacy and variability of the human touch in his iPad works. This is especially evident in a work like The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, 13th January 2011, where his limited palette of visible flicks, dashes and stippled marks echo the dynamic treatment of Vincent van Gogh’s natural landscapes, such as Country Road in Provence by Night (c. 1890). Hockney draws attention to these parallels through short, brisk strokes, accentuating his personal hand and emphasising his rapid, expressive way of working. The linework here is central to the composition and observational experience of this work, creating an effect which propels the viewer’s eye down the road. By using such visible marks, Hockney reasserts the role of the artist’s hand in the digital age, demonstrating that digital tools need not obscure this, but can in fact enhance the human elements in these artworks.

If you are intersted in adding to your collection speak to an art consultant today - info@halcyongallery.com